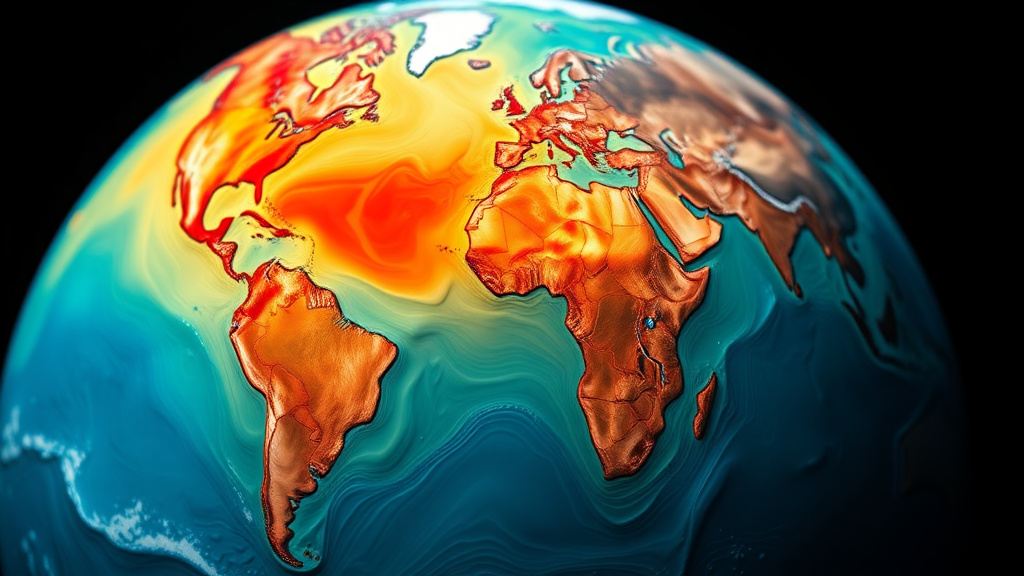

Earth’s climate system operates like a enormous circulation network situated below the waves. Recent groundbreaking research from leading climate scientists has unveiled the critical mechanisms by which ocean currents function as the planet’s temperature regulator, moving heat from the equator to the poles and profoundly influencing weather patterns worldwide. This article explores how these strong oceanic currents shape our climate conditions, why their disturbance creates significant dangers, and what scientists are learning about their role in controlling global temperatures for the centuries ahead.

The Vital Role of Marine Currents in Temperature Regulation

Ocean currents serve as Earth’s main heat transfer mechanism, moving warm water from tropical regions toward the poles while at the same time moving cold water back toward the equator. This ongoing circulation cycle, known as thermohaline circulation, is critical to maintaining the planet’s heat balance. Without these powerful underwater rivers, equatorial regions would experience extreme heat accumulation, while polar areas would remain constantly frozen. Scientists have found that even small disturbances to these currents can trigger significant shifts in climate patterns across regions and globally, influencing rainfall patterns, temperature swings, and seasonal climate changes across multiple continents.

The systems regulating ocean currents are exceptionally intricate, involving interplay of water temperature, salinity, wind patterns, and Earth’s rotation. Recent advanced modeling and satellite observations have enabled researchers to document these movements with extraordinary accuracy, demonstrating their intricate role in climate control. The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and the Pacific Thermohaline Circulation demonstrate how these systems convey thermal energy equivalent to millions of power plants. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for projecting future climate scenarios and comprehending how human activities might change these critical natural mechanisms that have preserved climate equilibrium for millennia.

Primary Ocean Current Systems and Their Roles

Ocean currents function as Earth’s principal mechanism for distributing heat, moving warm water from the tropics to polar areas while returning cold water to the equator. These interconnected systems function without interruption, powered by differences in water temperature, salinity, and wind patterns. The three major current systems—the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, the Pacific Thermohaline Circulation, and the Indian Ocean circulation—work together to maintain planetary heat balance and sustain environmental balance. Comprehending the mechanics of these systems is vital to forecasting coming climate shifts and their consequences for people around the world.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation System

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) represents one of Earth’s most important climate stabilizers, moving large amounts of warm water northward from the tropics. This current system comprises the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Current, which carry tropical heat to northern areas, making regions like Western Europe much warmer than their geographical positions would imply. The warm water eventually cools before sinking in the North Atlantic, initiating a deep return current that completes the circulation cycle. Scientists consider AMOC essential for maintaining the Northern Hemisphere’s climate conditions and regional weather stability.

New research has raised concerns about AMOC’s stability, as climate change drives freshwater inputs from thawing glaciers and higher rainfall. These freshwater additions lower water density, potentially weakening the sinking mechanism that drives the circulation. A reduction of AMOC could produce significant consequences, including reduced heat transport to Europe, altered precipitation patterns, and notable alterations in Atlantic hurricane activity. Climate scientists constantly assess AMOC strength through space-based monitoring and buoy array systems to detect any warning signs of disruption.

The Pacific Ocean’s Heat-Driven Ocean Circulation

The Pacific Ocean’s thermohaline circulation works as a significant thermal engine, powered mainly by differences in temperature and salinity rather than wind patterns alone. Dense, cold water descends in the North Pacific and the Southern Ocean, beginning a slow yet relentless deep-water conveyor that moves water through the basin over centuries. This circulation transports nutrient-rich deep water to the surface in specific regions, supporting productive marine ecosystems and fisheries. The Pacific’s thermohaline circulation significantly influences regional climate patterns, rainfall distribution, and seasonal weather variations in Asia, North America, and Oceania.

The Pacific thermal circulation system interacts dynamically with weather patterns and other ocean systems, creating intricate feedback loops that influence global climate stability. Variations in this circulation contribute to phenomena like El Niño and La Niña occurrences, which have global climate impacts. Scientists employ advanced computer models and observational data to understand how changing ocean temperatures and freshwater additions might alter circulation patterns in the Pacific. These investigations enable forecasting of likely changes in regional climates and their impacts on agriculture, water resources, and coastal communities throughout the Pacific region.

Environmental Effects and Future Implications

Ocean currents function as Earth’s primary heat delivery network, moving warm tropical waters toward the poles while sending back cold water to the equator. This continuous circulation regulates global thermal conditions and maintains climatic equilibrium across various areas. However, climate change could destabilize these fragile processes. Increasing levels of greenhouse gases warm surface waters, potentially slowing thermohaline circulation and weakening the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Such disruptions could lead to severe regional climate changes, including sharp temperature swings in Europe and changed rainfall patterns affecting billions of people worldwide.

Researchers forecast increasingly severe consequences if ocean circulation patterns keep declining. Weakened currents would diminish heat transport to polar regions, counterintuitively triggering freezing in some areas while accelerating warming elsewhere. These changes could devastate marine ecosystems, destroy fishing industries, and trigger financial instability across coastal communities. Comprehending ocean flow patterns remains essential for accurate climate modeling and developing viable solutions. Ongoing investigation and international cooperation are vital to averting irreversible damage to these essential climate systems and safeguarding coming generations from unprecedented environmental challenges.